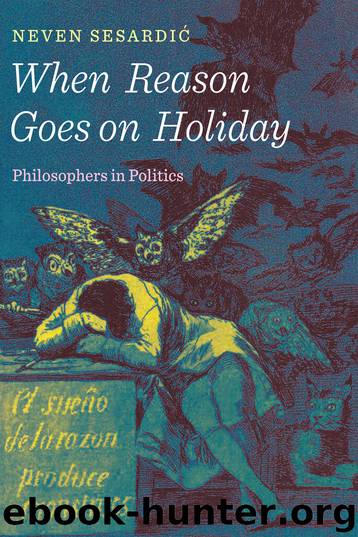

When Reason Goes on Holiday by Neven Sesardic

Author:Neven Sesardic

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781594038808

Publisher: Perseus Books, LLC

Published: 2016-09-29T16:00:00+00:00

A “Fascist Rebellion” in Hungary in 1956

Here is how Cohen describes his own reactions to two key historical events:

[T]he Soviet action in Hungary in the autumn of October 1956 was regarded, at the time, by virtually everyone in the party, as an entirely justified suppression of a fascist rebellion. I myself so regarded it at least as late as 1968. I recall contrasting it, then, with the invasion of Czechoslovakia that year [1968], which thoroughly rid me of my pro-Sovietism (Cohen 2001, 188).

Notice an inconsistency in Cohen’s report. He says that he regarded the 1956 Hungarian revolution as “a fascist rebellion” at least as late as 1968, whereby he obviously allows that he may have kept this view a bit longer—that is, after 1968. On the other hand, he claims he abandoned his pro-Sovietism thoroughly in 1968. Which is it?

Also, he says he remembers that in 1968 he contrasted the Soviet action in Hungary with the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, which seems to imply that at the time (in 1968) he actually had a very different opinion of these two events. Yet anyone who got pro-Sovietism “thoroughly” out of his system would have basically the same attitude to these two historical episodes. He would regard both the Hungarian revolution and the Prague Spring as legitimate battles against Communist oppression that were crushed by brute military force.1

That Cohen did not terminate his loyalty to the Soviet Union in 1968 is also supported by what Michael Rosen, his former Oxford colleague and now Harvard professor of government, wrote after Cohen died: “But even then [after the invasion of Czechoslovakia], I think, he was too much of a loyalist to make the kind of noisy break with the Party that the historian E. P. Thompson (and many others) had done” (Rosen 2010; emphasis added).

But there is a more pressing issue here. Although Cohen’s sincerity in reporting his past pro-Communist dogmatism may in some sense be admirable, the fact that he believed for years that what happened in Hungary in 1956 was a fascist rebellion is mind-boggling and defies easy explanation. How could such a thing be believed by someone who had studied at Oxford, who had taught philosophy for years at University College London, whose main research interest was politics, and who, after all (Cohen 2001, 26), had even visited Hungary himself in 1962? And what exactly could he have taught students about politics (or more specifically Communism, which obviously loomed large in his mind), if he could believe “at least until 1968” that the Russian tanks did a great favor to Hungary in 1956, saving it from fascism?2

Cohen also visited Czechoslovakia in 1964 and stayed there two weeks. He went out often, talking to many people about politics, and he says their response was always the same: “Going out and about the town, I found no one with a good word for the regime” (Cohen 2013, 17). And yet, even after witnessing the universal disillusionment with Communism in Czechoslovakia (and in all

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Hit Refresh by Satya Nadella(9133)

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi(8446)

The Girl Without a Voice by Casey Watson(7889)

A Court of Wings and Ruin by Sarah J. Maas(7845)

Do No Harm Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh(6941)

Shoe Dog by Phil Knight(5268)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(4969)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4963)

Hunger by Roxane Gay(4928)

Tuesdays with Morrie by Mitch Albom(4784)

Everything Happens for a Reason by Kate Bowler(4743)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(4588)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4478)

How to Change Your Mind by Michael Pollan(4356)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(4322)

The Money Culture by Michael Lewis(4207)

Man and His Symbols by Carl Gustav Jung(4135)

Elon Musk by Ashlee Vance(4127)

Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan by Jake Adelstein(3996)